Why a TED Prize Winning Platform May Inadvertently Rob Egypt of Its Buried Antiquities

[EXCLUSIVE] A TED prize winning platform is promising to teach anyone how to analyse satellite images to identify buried archaeological sites. The mission hopes to uncover and protect archaeological sites; but could it give looters the edge over the governments' lacking resources to protect them?

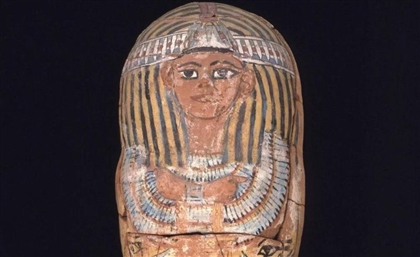

Egypt has been in a never-ending battle to protect its priceless history from both looters and decay since the age of pharaohs. However, in the age of technology, this battle is about to reach a pivotal turning point thanks to TED prize winner Sarah Parcak, who has created a new technique that will be available online and promises to turn anyone into a space archaeologist able to identify undiscovered heritage sites using space satellites from the comfort of their own home. On the surface, this powerful new resource is well-intentioned and could inspire a new generation of explorers and discoveries; but in an ailing post-2011 Egypt, could it have a disastrous effect in aiding looters to pillage Egypt - and other countries riddled with conflicts - of their ancient cultural treasures?

Currently, there are not enough safeguards in place to effectively combat looters in Egypt; the strategy currently employed seems to be focused on repatriating stolen artefacts after the fact, rather than preventing their theft in the first place. Providing the government with an opportunity to finally get ahead of looters is the University of Alabama at Birmingham's professor and pioneering space archaeologist Sarah Parcak. Her research has already uncovered 17 potential pyramids in Egypt, as well as thousands of forgotten settlements and lost tombs by using remote sensing infra-red images captured by satellites. After analysing the images collected from satellites as well as drone photos, Parcak’s then applies the data into an algorithm that detects subtle changes in vegetation and topography that often signals the presence of buried man-made structures.

Parcak claims her methods have been 90 percent successful in finding significant discoveries, although some Egyptologists, including an Egyptian archaeologist and co-founder of the Egypt’s Heritage Task Force Facebook site, Monica Hanna, believe Parcak's success rate may be exaggerated. “I heard about what Sarah was doing, but am a little skeptical as many of her discoveries have not been confirmed on the ground,” she says. Despite the criticism, several of Parcak’s findings have been confirmed, but with 1000 potential sites to explore, it will take time and plenty of resources to be able to confirm all her findings on the ground. However, the pressing issue at hand isn’t whether her method works, but rather the fact that she was awarded a 2016 TED Prize worth a million dollars to develop Global Xplorer, an online platform that will teach anyone the space archaeologist’s techniques to discover the planet’s unexplored potential archaeological sites, beginning with completely mapping out Peru and hoping to eventually cover the entire planet.

Although this wonderfully grand idea of creating an army of explorers could enter us into a new age of understanding the origin of mankind, it will also provide looters with the knowledge required to rob Egypt of its priceless heritage. “What she is providing is a double-edged weapon. Of course, I am in support of an open source platform that will help academics, but Egypt, Libya, Iraq, Syria and others will all face pandemic looting, which is already happening. The last thing we need, especially with the absence of law enforcement in unstable or conflict zones, is to tell looters where to exactly look,” explains Hanna.

As one of the few fighting on the frontlines in the war against looters in Egypt, Hanna and the Egypt Heritage Task Force have neither the authority nor the resources required to catch tomb raiders in the act, but have made it their mission to document the evidence, case by case, and learn as much as they can about these criminals and the organised network often employing them. According to Hanna, “There are different types of looters. There are the ‘villagers’, who are gangs usually made of family members like brothers or cousins, who go and excavate together in search of loot. Then we have the official mafia, that is an organised gang who receives funding, archaeological knowledge and are trained on how to use geo-sonars in the Gulf and abroad, and then come back ready to attack sites that have items they know they can sell.”

The latter looter is likelier to adopt Parcak’s methods and platform long before the common villager; in either case, the victim of these cultural raids is not only Egypt’s ancient heritage but also its present-day youth. “Sometimes, they use children, because they are small and agile enough to go down and bring up little objects. In Abusir el-Malek, I was told by several families in the village that around 25 children died helping looters in a single year between 2012 and 2013,” describes an alarmed Hanna. Even more troublesome is the fact that there is no true measure of the fatal devastation caused by looting, as families often refuse to tell doctors or authorities the truth about their deaths for fear of imprisonment. In the case of villagers, looting is simply the only means of survival, a desperate ploy to overcome the crippling economic conditions and attempt to make ends meet by any means. Organised criminals, on the other hand, are often employed by “collectors who are obsessed with a specific period and commission these gangs to go and loot. These gangs tend to jump between sites and the traces they leave are lunch boxes and very little evidence,” a disheartened Hanna describes. Aiding and abetting these criminals to smuggle these items out of the country is what Hanna describes as a “corruption network that existed even before 2011, though the amount of loot leaving the country wasn’t as big as it is now.”

In the case of villagers, looting is simply the only means of survival, a desperate ploy to overcome the crippling economic conditions and attempt to make ends meet by any means. Organised criminals, on the other hand, are often employed by “collectors who are obsessed with a specific period and commission these gangs to go and loot. These gangs tend to jump between sites and the traces they leave are lunch boxes and very little evidence,” a disheartened Hanna describes. Aiding and abetting these criminals to smuggle these items out of the country is what Hanna describes as a “corruption network that existed even before 2011, though the amount of loot leaving the country wasn’t as big as it is now.”

With looting already on the rise in a post-2011 Egypt, the pressure is mounting on the Egyptian government to provide a solution to a problem which is about to get a technological boost. It seems to be a safe assumption that the government isn’t prepared for Parcak’s revolutionary platform. As Hanna points out, “the government knows exactly what sites are being looted, but they do not have the resources or the know-how to deal with it. People are excavating one kilometre away from the Pyramids, and yet nothing has been done.”

Coupled with the variety of problems Egypt is trying to overcome, when it comes to archaeology, preservation trumps excavations, as even the Valley of Kings is degrading at an alarming rate because of the all-time low in tourism whose money is used to maintain these sites. “When I started in this business 34 years ago, tourists could cover all 62 tombs going from one room to another. We learnt over the last 10 years or so, that the masses of the groups coming in were generating so much heat and perspiration that they were providing the elements for fungi to grow, damaging these sites,” explains veteran freelance Egyptologist Sherif Samy. In an attempt to slow down the degradation, the government only allows access to 6 or 7 of the 62 tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

As it stands, what mankind have discovered of Egypt’s Ancient past is only a fraction of what remains buried, as Parcak estimates that “less than 1 percent of ancient Egypt has been discovered and excavated.” But this claim is extremely difficult to confirm, as looting has been taking place for centuries and there’s no telling of how much of Egypt’s history has been lost.  To effectively stop looters before the damage is done, multiple ministries will have to work together and present a grass roots approach that financially improves the livelihoods of villagers, possibly turning villager looters into Egypt's first line of defense against organised network. “If people are making money out of cultural heritage they will be the first to protect it. We need to introduce small projects that will improve the livelihood of villages that contain cultural heritage components and through working with the community we can start protecting these sites. No security measure will stop the looting unless we decide to invest in economic development and education,” Hanna believes.

To effectively stop looters before the damage is done, multiple ministries will have to work together and present a grass roots approach that financially improves the livelihoods of villagers, possibly turning villager looters into Egypt's first line of defense against organised network. “If people are making money out of cultural heritage they will be the first to protect it. We need to introduce small projects that will improve the livelihood of villages that contain cultural heritage components and through working with the community we can start protecting these sites. No security measure will stop the looting unless we decide to invest in economic development and education,” Hanna believes.

This may not solve the problem overnight, but over time could provide vulnerable archaeological sites with a local security network that can detect strangers in the area and alert authorities before they illegally excavate. However, time is not on Egypt’s side as Parcak’s online platform is reportedly launching early this year. Technological advancement is inevitable and shouldn’t be stopped but rather prepared for. In Hanna’s opinion, “What we need is a grace period of 10 years so things can stabilise, and then after that, you can put whatever resources you want online. In moments of conflict and unrest, I think it becomes a naïve project that will only lead to more looting, which is obviously not the project's intention.” Hopefully, the platform will implement strict registration process to weed out potential looters and the program will coordinate with UNESCO to ensure that discoveries made are protected before being mapped out.

The Global Xplorer platform idea is noble, but a much larger debate is required as its implication will affect several countries that will not be able to secure these discoveries during times of conflict. “People in conflict situations become responsible for their cultural heritage and need to step up and protect it when the government isn’t doing their job properly. It becomes a responsibility for all of us, and I urge everyone to stand up and help,” an adamant Hanna expresses.

In a perfect world, Egypt’s government would embrace this platform, secure new sites discovered, and even implement the use of social media during new excavations to inspire archaeologists and tourists to visit. But this isn’t a perfect world and as it stands Egyptians don’t care about their heritage as much as foreigners do, which is why Egyptians would often rather focus on education and its ailing economy before seriously tackling this incredibly difficult and technologically evolving looting problem. It is for these reasons Global Xplorer, although revolutionary and well intentioned, is destined to fail in protecting these sites, as it will give looters an upper edge in a battle that governments in conflict zones have few resources to fight.

Photos retrieved from Google Earth and Egypt's Heritage Task Force Facebook Page.

Trending This Week

-

May 01, 2024